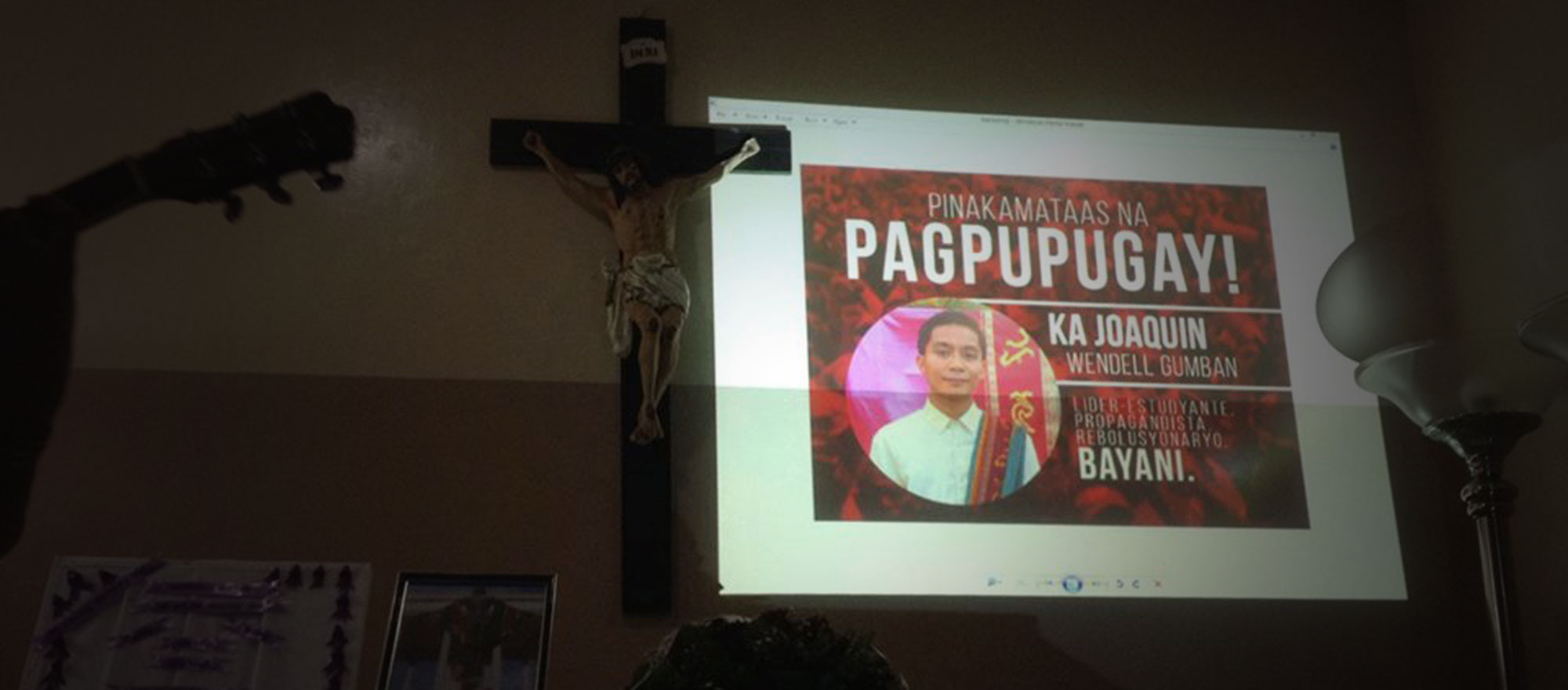

In Memory of Wendell ‘Ka Waquin’ Gumban

Wendell, or Waquin to his comrades, was a scholar of the people who left his petty-bourgeois life to serve oppressed workers and, later, landless peasants and indigenous people–as a guerrilla of the New People’s Army.

by Ka Ben

I first met Wendell back in 2009 when he was in the Public Information Department of national labor center Kilusang Mayo Uno. I instantly liked him; he had a nerdish, yet cool, persona. He reminded me a bit of Clark Kent–bookish, introverted and masked a hidden strength that I would much later come to know. His daily schedule consisted of waking up at around 10 in the morning and typing out press releases and other propaganda materials sometimes until the next morning. He was a hard and tireless worker and gifted writer. He could do anything he put his mind into.

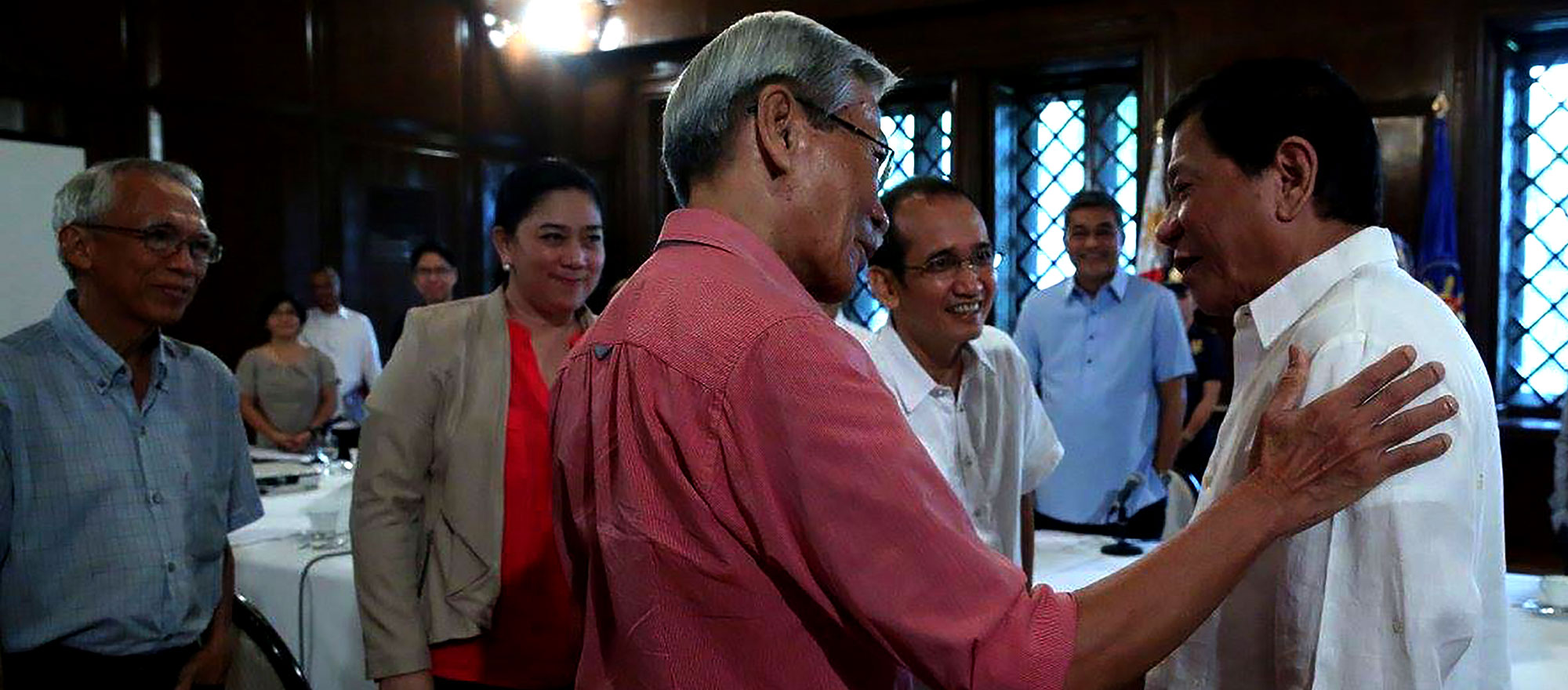

![]() He had distinct, very funny and likeable mannerisms that ingratiated him to me. He occasionally squealled, “Ahhhhhhhaaaaaa!”–a distinctive sound that elicited smiles and laughs from those around him. Unlike other comrades who would dance around the edges, I could always count on Wendell to be brutally honest in his comments and analyses. He had no fear of offending you and did not shy away from talking about his own weaknesses. He always had a healthy dose of cynicism. What you saw with Wendell was what you got; there was no grey area and you could always trust him to give you an accurate account of the lay of the land. He became a very good and trusted friend and kasama because of this. We were both outsiders in our own distinctive ways and this cemented our friendship.

He had distinct, very funny and likeable mannerisms that ingratiated him to me. He occasionally squealled, “Ahhhhhhhaaaaaa!”–a distinctive sound that elicited smiles and laughs from those around him. Unlike other comrades who would dance around the edges, I could always count on Wendell to be brutally honest in his comments and analyses. He had no fear of offending you and did not shy away from talking about his own weaknesses. He always had a healthy dose of cynicism. What you saw with Wendell was what you got; there was no grey area and you could always trust him to give you an accurate account of the lay of the land. He became a very good and trusted friend and kasama because of this. We were both outsiders in our own distinctive ways and this cemented our friendship.

He lived simply. He did not drink and only very infrequently did anything socially. His only vice was taking ridiculously long baths. His life was the KMU office, just as it would later become the guerrilla fronts he was deployed to. We occasionally got out for a meal at a local carenderia and chew the fat. I once had the privilege of spending a weekend with Wendell’s family, who were loving and supportive. He was very lucky and my heart goes out to them now for their loss. If it is any consolation, many of us feel their loss and pain. Wendell was loved by so many people both in Manila and the mountains of Compostela Valley and Davao Oriental that became home for him.

I did not meet Wendell again until 2011. We met again in the most unlikely and special of places. Like him, I had decided to go to the countryside. I found myself deployed to Southern Mindanao. After a three-hour car ride to Compostela town, I was put on a motorbike (habal-habal) for a two-hour journey along mountain passes and what were once logging roads. We reached a tiny purok, of about ten houses and one karaoke bar. We walked up a small hill for 15 minutes where we reached the camp of Front 25 of Sub-region 1 – the same front that was led by the legendary Party secretary Ka Pakeng and also where a former mentor of Wendell’s would later become the secretary after Pakeng was martyred.

It was an undersized company formation of two platoons. The first thing I realized was “Yikes, this camp exists in a foot of mud!” I thought, “What have I gotten myself into?” As I struggled to walk in the mud and not being able to communicate with most of the kasamas, I was suffering from extreme culture shock. And then as I made my way through the camp, there, sitting in his duyan, looking as content as ever, was Wendell–now named Ka Waquin (read Joaquin). He said, “Wow, it is really you! Fancy meeting you here, of all places!” I responded, “I’m so happy you are here!” I was beaming. Waquin helped me to adjust to my new life as a red fighter, and without him it would have been so much harder. That first night in the camp was surreal. We could hear the karaoke bar below us repeatedly playing “Pusong Bato“. We stayed up talking about his new life as a red fighter.

He also inquired about our friends back in Manila. He loved to be updated on chismis (gossip). He confided that when he first rang his parents about his decision, they cried. But they slowly came around to accepting his new life. By this stage, he had been a red fighter for a year and was tasked with organizing education in the front. He was very comfortable in his new life as a guerrilla. Unlike other kasamas who came from the student sector, he never asked for sweets or city food and luxuries to be sent to him. He wanted to live and be treated the same as any other peasant comrade. So that meant usually eating bulad (dried fish) and noodles for breakfast, monggo for lunch, and sardines and noodles for dinner. Occasionally, the comrades would kill a milo (civet cat) and we would eat that. It had a horrible, musky taste, but we still ate it just to have some variety. Once a week, we would have a proper meal, maybe fish ginataan or chicken adobo, and Waquin would eat very slowly and loudly exclaim “Mmmmmmm!”, savoring every bite.

I assumed his new name was Arabic, so I asked him why he chose that name. “Oh, it means ‘Wak-Wak Queen!” he beamed. He had a healthy dose of humor and was a fantasist of sorts. Wendell the Wak-Wak Queen of Mt. Diwata!

By that time, he had already developed a deep understanding of guerrilla warfare and base-building. Front 25 was in the mountainous boundary of Davao Oriental and ComVal. The Diwata mountain range cut through it; the terrain was extremely favorable to guerrilla warfare and it was a strong, consolidated base area. The people there were Lumad. The comrades had been there for more than 30 years. Visually, it was beautiful. We would march through small villages with curious eyes and beaming smiles while venturing up impossibly high mountains, with waterfalls and the sounds of the forest all around us. It was physically challenging, but good for the soul.

I remember we were once chatting about the masa and I said, “You know, in the cities, it is so difficult. The revolution is very abstract to the urban poor masa. Their life is a living hell in many ways, but it’s hard for them to imagine a different way of being.” Waquin chimed in. “Here, it is different. Here, the people cannot imagine life without the comrades and the revolution.” The flip side to that was they were often just happy to have the comrades around to help them in their daily lives and struggles, rather than think about the overthrow of a very distant reactionary state. Waquin saw the importance of his task as an educator who assists the people in raising their consciousness on the long-term gains of the revolution and on the need to not to be content with just the here-and-now.

He always had time to talk and give advice to his fellow red fighters, help them with their literacy and learn about their lives before they became revolutionaries. He helped educate the masa through community theater, education courses or through just engaging in daily chit-chat. Waquin was respected and loved by the masa he came to know. They said, “Wow, a university graduate has come here all the way from Manila! Thank you for joining us here!” The camp was usually busy with activity. The masa would turn up and ask for advice on a variety of issues, including land disputes, intrigues in the village, the encroachment of mining corporations, problems with local merchants, local criminals, and military abuses. He was willing to analyze and come up with ideas and solutions to the various problems and struggles that the masa presented to him.

He always volunteered to be part of military work, and excelled at tactical offensives and ambuscades. He was always cool, calm and collected. We did the advanced military course of the region, and it was very physically demanding. We were covered in mud from head to toe for a month. We pushed ourselves to the limit. Unlike me, he could do everything. He was remembered for doing his military formations with his knees going up higher than anyone else – much like he was marching in a brass band.

It was not always about the serious work of being in a life-and-death revolution. Waquin once confided in me: “You know, it’s very nice here. In TU (trade-union movement), no one paid any attention to me. But here, the kasama tells me I’m gwapa (pretty). I feel so beautiful.” Unfortunately, to my knowledge, Waquin did not find true love in the countryside. He did, though, have to struggle with shooing away an oddly opportunistic admirer who attempted to climb into his posting in the dead of the night.

Once, we hiked for two days to go into the very remote Mandaya heartland. The place was magical, with the last remaining rainforests. A whole squad could stand around the girth of a tree. We camped next to a waterfall and rock pools. Waquin told me that when everyone was asleep he would sneak out to the rock pool and swim naked, floating on his back staring up and mesmerized by the light of the moon.

After I had been in the front for a few months, Waquin was promoted to the position of “political instructor” and was brought to the front committee. In this role, he was indispensable to the further consolidation and expansion of the front and mass base. His honest insights were always appreciated. Because he was close to many of the kasamas, he always had the pulse on what was happening and it was useful in helping them overcome their personal struggles.

I remember, once he was tasked with organizing a wedding for two comrades. This was a task that he relished and took very seriously. He made beautiful bouquets of flowers found in the forest, and decorated the whole camp. It was a fantastic occasion and the front secretary commented, full of admiration: “What a comrade! He can ambush, educate, write and now he’s a wedding planner!” We were all proud of him. But during the planning of the wedding, he decided to one day wear a chiffon sarong as a mini-skirt. We did not want to stop him from expressing himself. But most of us were nonetheless relieved that the mini-skirt was worn for just that one day, and then replaced with the more conventional hiking shorts and botas (boots) the next. Anyone who had seen his chicken legs will understand why.

I was transferred to another military unit after about five months, but we would keep in touch every now and then. I would try to assist him with requests he had.

Although his death is heavy and, of course, very sad, and despite us being close friends and kasamas, I have yet to cry. If his death had been a senseless one, I would. But it was anything but senseless. Wendell found himself in the people’s war, as a red fighter among the mountains and people he loved so much. He chose to live his dreams and that is something to be admired and emulated. Although he has been taken from his loved ones too soon, they can find solace in the fact that he led his life fully as part of a living and breathing revolution.

In our guerrilla fronts, when a red fighter falls and when the situation allows, we get together and remember them and their ultimate sacrifice and martyrdom. Every comrade will speak of the times they had together, both the difficult and the joyful and what they had learned from the fallen comrade. A kaleidoscope of emotions explodes. We celebrate their life and the times we shared together in the service of the revolution. We gather from this the strength necessary to persevere and fight on.

Wendell was very loved by the Lumad communities of Sub Region 1 of Southern Mindanao. He made an impact wherever he went. Like me, the Lumad and peasants will also be speaking his name and remembering him fondly for many decades to come. To give your life for the people and that dream of liberation is monumental. Dugang kadasig!