What we stand for when we stand with the Lumad

A massacre in a Surigao del Sur tribal school implicates the state and challenges the citizenry. Finally, the Lumad struggle becomes a national one.

That #StopLumadKillings managed to break through the mainstream’s wall of chismis and love teams is a welcome development. It is laudable that reportage—and, as a consequence, public awareness—on the Lumad struggle is increasing. Much of the widespread empathy and concern generated by the campaign is beautiful, a show of humanity that is especially valuable to the Lumad people whose struggles have long been relegated to the sidelines of national attention. Knowledge and compassion, after all, set the stage for action, and the Lumad campaign is fraught with issues that need both our urgent and long-term attention.

One bothersome inflection of opinion raised by the campaign, however, is the problematic specter of the “indigenous,” that is, how we generally perceive ethnolinguistic groups that are neither Christianized nor “modern.” What are indigenous people anyway? Are they mere archetypes that we can conjure whenever we need to project an image of “nation” and “Filipino culture”? Are they reducible to mere artifacts and costumes, pawns for tourism, nothing but local color? Are they backward people, unable to uplift themselves and incapable of self-determination—and, in the context of #StopLumadKillings, desperate for our rescue from the crossfire in a raging war?

There is a need to emphasize: Lumad people are neither docile nor helpless. That they can evacuate together hundreds of families at a time speaks of how they are organized, tight-knit, and decisive. They possess individual agency as much as any other Filipino citizen, perhaps even more. The history of Mindanao is one of resistance, and paradoxically, coexistence; this is not something that happened by accident. The Lumad, along with the rest of our indigenous groups, have struggled to keep colonial powers largely at bay, and in a world continuously rampaged by Western cultural hegemony, they have managed to maintain their traditions and culture and remain attuned to their environment—something that cannot be so easily said for their lowland brothers.

Given the government’s lack of social services for the Lumad people, for example, they established their own tribal schools like Alcadev, each with a unique curriculum grounded on their culture and way of life. The military argues that these schools are rebel schools; they are right, not because tribal schools train rebel foot soldiers, but because they forge a counterculture that challenges the dominant narratives of education in the service of capitalism as the sole valid benchmark of development. Alternative schools set the condition for alternative ideas, which subsequently create the possibility for alternative realities. When we rise to #SaveOurSchools, we defend not just the physical schools which the Lumad built from the ground up; we also defend their schools of thought, and the promise of change that they contain.

It is telling that a large percentage of the goverment’s priority large-scale mining projects are in Mindanao, and not quite coincidentally, around 60 percent of the Philippine Army’s forces are deployed in Lumad areas. A DOST presentation of the state’s “Whole of Nation Initiative” highlights an “IP-centric” approach in Eastern Mindanao, citing that majority of New People’s Army members are indigenous peoples, and that almost all guerrilla bases are in indigenous territories. The government, indeed, is conveniently maneuvering its full-scale war against Communist rebels as a smokescreen for protecting a conflation of state and private interests. Clearly, the state recognizes that Lumad lands are hotbeds of both wealth and resistance. It is an insult to the Lumad peoples’ agency to imply that they are hapless tribes in need of saving, merely caught in the middle of warring factions when they are, in fact, at the center of the war itself.

Neither are the Lumad infallible to the allure of wealth and power. The AFP-sponsored paramilitary groups count Lumad members among their ranks, and these groups are behind some of the most gruesome human rights violations of late. Many have called for the disbanding and disarming of these militia groups, calling their very existence divisive. The state’s veiled support for paramilitary groups anoints them with power and impunity, and the prospect of such power corrupts and fractures communities, pitting kin against kin. Mining and logging projects, with their rosy promises of wealth and employment and token scholarships for affected communities, have likewise divided families and tribes, some choosing the path of resistance, some opting for cooperation and capitulation.

The prime example of Lumad fallibility is the chair of the House Committee on indigenous peoples herself, North Cotabato Rep. Nancy Catamco. The self-proclaimed Diwata has a nose for scandal: Catamco is embroiled in major controversies like Joc-Joc Bolante’s fertilizer funds and Janet Napoles’ DAP. Among her numerous botched endeavors is the “rescue” of Lumad evacuees in Haran, where, in a gesture so absurd one wonders if it is naive, ironic, vicious, or all three, Catamco brought in the police and military as “rescuers” to bring back the Lumad to their communities, when they were the very elements the Lumad were fleeing from in the first place. Under Catamco’s custody, a “rescued” 14-year old Manobo girl was raped by three military men, but no charges were filed by the parents who settled for the measly sum of roughly P60,000. Also under her protective custody is a suspect in the brutal murder of Italian missionary and anti-mining advocate, Fr. Fausto “Pops” Tenorio, who was peppered with bullets by Lumad militia right outside his Arakan Valley parish. In the wake of the recent killings and evacuations in Surigao, Catamco brazenly exploited her Manobo lineage to call for the government to recognize and support, even supply Lumad militia with arms.

Greed and corruption know no tribe. Fortunately, neither does the power to fight back. When we proclaim #StopLumadKillings, we must do so not out of pity, but solidarity. By overcoming our differences in identity and coalescing under a single call, we recognize the Lumad struggle as vital to our collective integrity as Filipinos.

In the twilight of the Aquino regime, the Lumad campaign paints the sky a blazing red against the setting of the yellow sun. It is, perhaps, the most sweeping struggle under the Aquino administration, which forged the paths of lucrative public-private partnerships, widespread corruption, criminal ineptitude on social services and aid, and gross human rights violations under Oplan Bayanihan. With #StopLumadKillings, all of these inroads converge into one bloody juncture, a veritable roadmap of the storied Daang Matuwid. Presidencies end, economic miracles pass unfelt, but a regime’s bloody human rights record will remain its most lasting legacy, for the sorrow of families and communities leaves a long wake that ripples through generations.

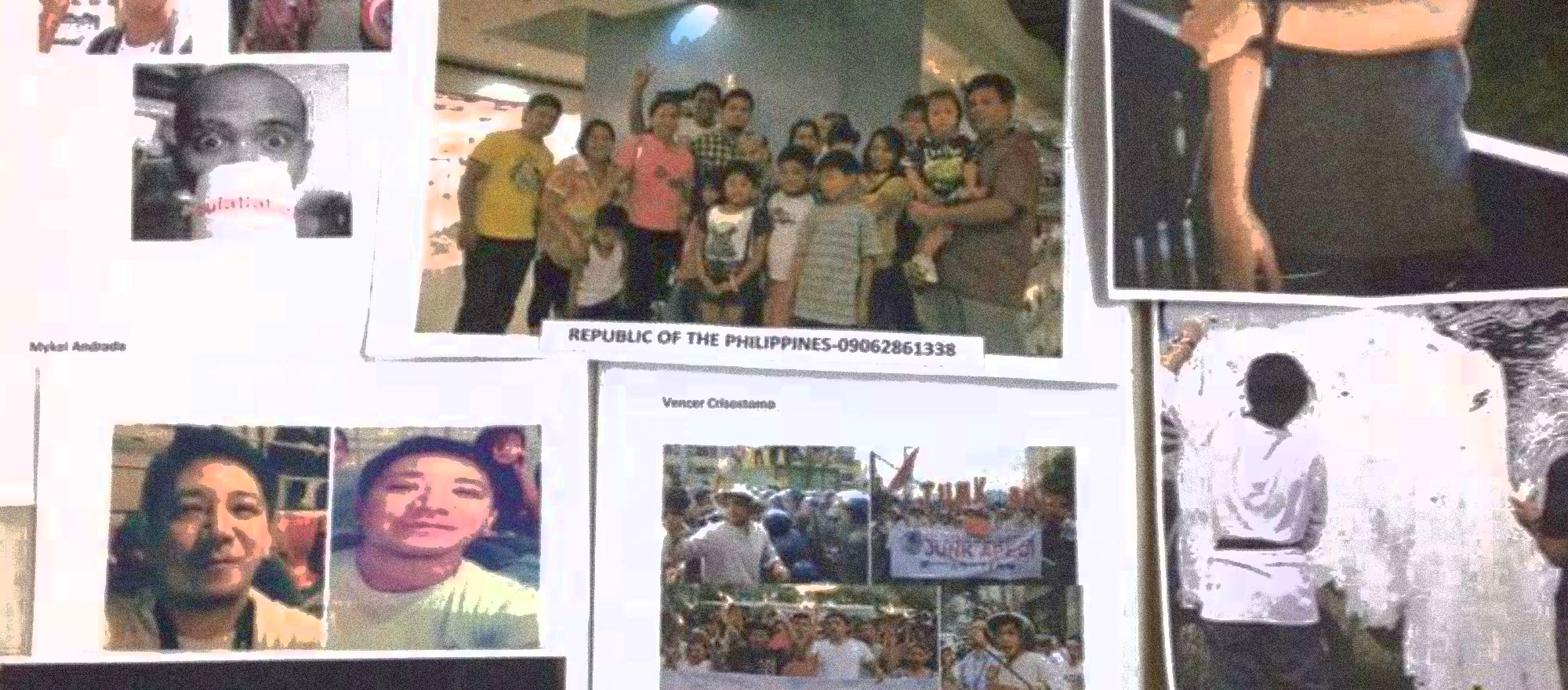

In the coming days, we will hear them say it’s just a tribal war. That leftists are hostaging the bakwit and using them for their own evil agenda. That hordes of Lumad are being coerced into joining anti-government rallies. That Alcadev is an NPA school that teaches farming on weekdays and rifle marksmanship on weekends. The allegations will probably get more and more absurd, more shocking, more unbelievable, as unbelievable as the dubious social media accounts and websites that will mushroom and spout these speculations.

Confusion will be sown in an attempt to obfuscate truth. But there are certain truths that cannot be obscured, not by any amount of smoke, mirrors, or blood.

Like the truth that they once rounded up a whole village and made them watch as their leaders were beaten and shot. Or that they colluded to rip out a tribe’s heartland so they can exhume its treasure, all the while assuring us, the overall visual impact of the Project would be low. That they deployed thousands of men clad in the colors of the jungle, destroying everything they deem red while protecting everything that glints of gold.

Or that a woman wailed kneeling in front of a dead teacher, her pained voice breaking as she stroked the silver hair streaked with blood from his slashed throat, assuaging him, and perhaps her fellow survivors too, that You will not be forgotten. We will persist and be stronger. You are part of the life of Han-ayan.