FQS and the continuing tradition of the revolutionary youth

I just finished reading Jose “Pete” F. Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage, a chronicle on the First Quarter Storm (FQS) of 1970 which happens to be 45 years old this 2015. I had been looking for a copy of the book before but unlucky to find one. A colleague was able to find an […]

I just finished reading Jose “Pete” F. Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage, a chronicle on the First Quarter Storm (FQS) of 1970 which happens to be 45 years old this 2015.

I had been looking for a copy of the book before but unlucky to find one. A colleague was able to find an old edition in a secondhand bookshop in the Manila City Hall underpass and lent me his copy.

I was beaming with excitement as I carefully flipped through the frail pages of the book. A side note, I was thrilled to learn the details of the protests in Lyceum of the Philippines, my alma mater, which was one of the bastions of the student activism along with the University of the Philippines and Philippine College of Commerce (now Polytechnic University of the Philippines). I was not able to sleep until six o’clock in the morning because I really wanted to finish the book.

The demonstrations took place in Metro Manila from January to March 1970, hence the name First Quarter Storm or Sigwa ng Unang Kuwarto in Filipino. With the youth at its forefront, it ignited the anti-imperialist and anti-fascist sentiments that spread like wildfire across the archipelago. The protests, usually attended by thousands of students, urban poor, workers, and peasants, opposed anti-national and anti-democratic policies of the President Ferdinand Marcos such as US intervention and the Philippine participation in the Vietnam War. They also demanded a non-partisan Constitutional Convention, among other calls of progressive people’s organizations. At that time, Marcos was eyeing for a third term and wanted to manipulate the Con-Con in his favor.

It all began on January 26, 1970, when Marcos delivered the State of the Nation Address opening the session of the Congress. Coming out of the Congress Building (now the National Museum) to their car, Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos was assaulted with two mock objects from the demonstrators: a coffin signifying the death of democracy and a crocodile for the greed of the government and its officials. After the Marcos couple left, police brutality ensued and several activists were bludgeoned, shot at and arrested.

After the January 26 incident, the protests numbered from fifty thousand to a hundred thousand and enjoying popular support of the masses. The Movement for a Democratic Philippines (MDP) organized various protest centers in Metro Manila and converged in Plaza Miranda or another rallying point and marched to the strongholds of reactionary power such as the US Embassy, Malacañang Palace, and Congress Building.

FQS, for a young person like me, is hard to imagine merely by reading. I listened to personal accounts of activists like Satur Ocampo, who hailed from Lyceum and PCC, about their experiences during that time of social unrest and upheaval of the youth and labor groups before the declaration of Martial Law by Marcos in 1972 which further plunged the country into deeper economic and political crises.

During the Cinemalaya Film Festival in 2010, I was able to watch Joel Lamangan’s Sigwa, a film about the youth movement and FQS. I was not an activist then, as I was just a journalism student from Lyceum. I was not able to grasp the concept of the need for revolutionary violence and people’s protracted war against a fascist government. Characters in the film kept on saying words like burgis, imperyalismo, and pasista which were unfamiliar to me years ago. But the message of need to defend the rights of the people against an oppressive regime was clear.

Pete Lacaba’s account of FQS provided me with a different insight, as if I was there in the streets of Manila during those confrontations with the Philippine Constabulary (PC) and the Metrocom. He effectively illustrated through words the events which inspired the youth and people to join in the struggle for genuine freedom and national democracy.

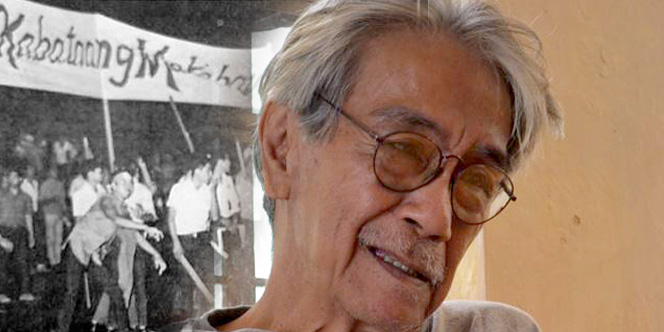

As Jose Maria Sison, founding chairperson of Kabataang Makabayan (KM), said in his statement on the 40th anniversary of FQS in 2010, “The First Quarter Storm of 1970 was the highest point of the legal democratic mass movement for national liberation and democracy before the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in 1971 and the declaration of martial law in 1972. It put forward the patriotic and progressive demands of the people against US imperialism and the local exploiting classes.”

Sison added that FQS “raised the fighting spirit of the broad masses of the people against the US-directed Marcos regime and against the repeated threats of the regime to declare martial law. It pushed the organized forces of the national democratic movement to accelerate their political and organizational work among the people.”

During the FQS, youth organizations like KM and Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK) became stronger nationwide, attracting members from public and private schools, factories, and urban poor and farming communities. They organized and educated not just the youth but also workers, peasants, and indigenous peoples.

FQS developed mass activists from the students and intellectuals and reinvigorated the national democratic struggle in the cities and countryside. Later on, their efforts paid off with the increased number of Filipino youth and people joining the armed struggle of the New People’s Army (NPA) against the US-Marcos regime.

The Diliman Commune of 1971 and FQS of 1970 may be a thing of the past for some old timers, but these events sparked the Filipino people’s struggle for national democratic demands. These events are still important and relevant today by providing the Filipino youth with valuable lessons from the history of the national democratic movement and the strong ties of the youth with the laborers and peasants to build a strong alliance against imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism.

Forty-five years have passed after the FQS, the condition of the Filipino society remains the same, as those regimes after Marcos continued to serve not the democratic aspirations of the Filipino people, but the dictates of their imperialist overlords. The call of FQS for national liberation and democracy still echoes in the streets and hills today.

As Sison said in his statement in 2010, “We must celebrate the great significance and continuing relevance of this historic event. We must renew our resolve to carry forward the Filipino people’s democratic revolution against US imperialism and the local exploiting classes of big compradors and landlords.”