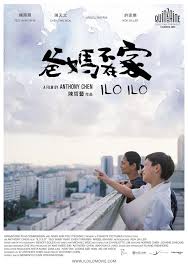

Ilo Ilo: The Movie (Review)

by Delia D. Aguilar* Loosely based on his childhood experience with an Ilongga yaya, “Aunt Terry” in the movie (Teresita Sajonia of San Miguel in real life), Singaporean first-time filmmaker Anthony Chen’s “Ilo Ilo” received the Cannes’ Camera d’Or award in 2013. It also garnered a slew of rave reviews from critics worldwide. One of […]

by Delia D. Aguilar*

Loosely based on his childhood experience with an Ilongga yaya, “Aunt Terry” in the movie (Teresita Sajonia of San Miguel in real life), Singaporean first-time filmmaker Anthony Chen’s “Ilo Ilo” received the Cannes’ Camera d’Or award in 2013. It also garnered a slew of rave reviews from critics worldwide. One of the latest, an April review in NY Times printed to announce its showing in Manhattan, describes it as “an acutely perceptive examination of middle-class life” set against the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

This crisis shapes this simple, straightforward narrative as it revolves around the quotidian struggles of a striving couple, their brat of a son, and their domestic helper (skillfully played by Filipina actress Angeli Bayani) who deals with her employers with infinite patience, if not the obsequiousness, that is a prerequisite for the job. The husband who is employed in sales gets fired; worse, his reckless gambling results in a sizable loss in the stock market, a secret he attempts to keep from his wife. The wife is a hard-working secretary whose task, not without a touch of irony, involves sending out termination letters.

The entry of Aunt Terry into the household is what draws the audience’s attention as it proceeds to alter family dynamics. The yaya is made to room with 10-year-old Jiale whose spoiled-brat conduct she quickly learns to handle deftly, an accomplishment that we fully expect to perturb the mother, which it does. It goads good old Mom to assert her superiority over the migrant woman in ways big and small.

This is the gist of the story. But what does it have to do with Iloilo? Not much. In fact, Iloilo is never mentioned in the film; it is only implied when Aunt Terry makes a phone call in Hiligaynon that she has a child of her own left behind. The Chinese title, translated, is “Mother, Father, not home.” From this one might reasonably surmise that the oddly spelled “Ilo Ilo” has been contrived for exotic effect.

Needless to say, the film was a success. At Cannes, it received a 15-minute standing ovation, stopped only at the crews’ request as the members had to leave for another engagement. At the UP Film Center in Diliman where we viewed it last February, the mostly student audience stood up and clapped at the end. Now why was approval from this specific audience, not that of the critics, unsettling for me? Surely they appreciated the movie’s craftsmanship just as the critics did. The applause may even have been primarily for Angeli Bayani’s superb performance.

Maybe so. But let’s not forget that Singapore in 1995 was the very scene of real-life domestic worker Flor Contemplacion’s execution. Her judgment and sentence were met with huge protests in the Philippines, which in turn forced then President Fidel Ramos’ unsuccessful intercession. Shortly after, Nora Aunor starred in a documentary depicting the case, winning her an award in Cairo. If all this was lost on the students because they were only born that year (as a young UP professor tried to explain), surely they couldn’t have missed the recent news item about domestic worker Ina Francisco who accused her employers in Malaysia of applying a hot iron on her back and arms. In short, they–in truth, all of us Filipinos–should have some knowledge and an informed opinion about the lives of our fellow citizens scattered about in every corner of the globe in search of jobs.

We do have that information. The problem is that the whole situation—the export of cheap labor that began with the 1974 Labor Code known as Presidential Decree 442 and the remittances on which the Philippine economy has become dependent—has been so normalized that we no longer question the policy. The remittance figure for 2013, $22.8 billion, exceeded by 6.4% that of the previous year. It is no exaggeration that without these remittances the economy would collapse, a fact that everyone in the Philippines accepts. It has been said many times before, but it bears stating again: the kind of “development” we have is one that has been literally built on the backs of domestic workers. Remember how President Cory Aquino hailed domestic workers as “modern heroes” and President Gloria Arroyo called for the training of Filipina domestics as “supermaids”?

Set against this backdrop, let me return to Anthony Chen and Teresita Sajonia, the nanny his film character is based on. Chen was 4 when Sajonia joined the family, 12 when she left. Because of the movie, Chen, now 29, and Sajonia, 56, see each other again after 16 years in a meeting arranged in Iloilo by a Chinese businessman. Chen is struck by Sajonia’s poverty and how old she has become, looking 65 and not the 56 that she is. He can’t believe how drastically her life has changed. Her home is only a hut built with wooden planks and bamboo. She used to buy hi-fi sets to send home, he recalls; today her room is bare with just a lightbulb and a transistor radio, “no proper stove, no proper drinking water.” Taken to a restaurant, he observes that she doesn’t even know how to push the button on the elevator anymore. Most shocking for Chen was that she used to speak good English, and now she’s forgotten that as well. In sharp contrast, it seems that “Aunt Terry” always remembered her employers. Chen notes that she was “carrying this pouch my mother gave her…[containing] photographs of our family.” Such devotion naturally merits rewards, and so the magnanimous Chen in the end favors Sajonia and her husband with a bank account; has them fitted with new glasses; and gives her a pig which, after all his prodding, is all she desired.

About Iloilo residents, Chen remarks that the people are passionate about the film because “all of a sudden, the world knew where Iloilo was and it was through a Singaporean film.” For this, are you properly grateful to Anthony Chen?

It’s been said that the subaltern can not speak for various reasons. The movie, on the surface “true to life,” left a whole lot of subaltern history out. When the students clapped, they unwittingly obscured the story behind the scenes, as it were. It is this history we need to dig up and talk about loudly as a community.

*Prof Delia Aguilar is formerly Irwin Chair Professor of Women’s Studies, Hamilton College, and adjunct professor of Gender Studies, University of Connecticut.”